‘Blessed are the young, for they shall inherit the debt,’ quipped America’s 31st president, Herbert Hoover. In Australia’s case, the inheritance is far more generous, though not in a good way. Alongside eye-watering public debt, the next generation will receive a tax system so convoluted it could double as a punishment, a regulatory maze seemingly designed to asphyxiate productivity in red and green tape, and an education system where mediocrity isn’t the exception but the goal. And just to round things out, the young will also get a top-heavy political and bureaucratic class, brimming with self-assurance and zero skin in the game, who are convinced they understand business better than the people who actually take the risks.

It is a grand legacy of well-meaning intentions, wrapped in dysfunction, tied with incompetence, and handed down like a family heirloom nobody asked for.

Australia is now facing chronic budget deficits, enormous national debt, and arguably the most fiscally delinquent government in half a century. All generously matched by an opposition so devoid of conviction, one wonders if they are just waiting for their turn to torch the treasury again. And let us not pretend this descent into fiscal chaos happened in a vacuum. The Australian electorate has not merely tolerated this behaviour, but it has applauded it, gleefully rewarding sugar-hit spending sprees with electoral success.

Once upon a time, structural safeguards enforced some fiscal discipline. The Loans Council, which restrained state and territory borrowing, was quietly euthanised by the Keating government in 1993. In 2007, the Rudd government introduced a federal debt ceiling, which, while imperfect, at least gave a nod to prudence. It was unceremoniously dumped by the ‘fiscally conservative’ Abbott government in 2013, with the support of the Australian Greens.

Now, all constraints, bar a bond market revolt, are off. Australian governments face no serious barrier to spending like drunken sailors on shore leave. Reckless outlays are not just permitted but effectively required. The political cost of saying ‘no’ to spending is far higher than saying ‘yes’ to insolvency.

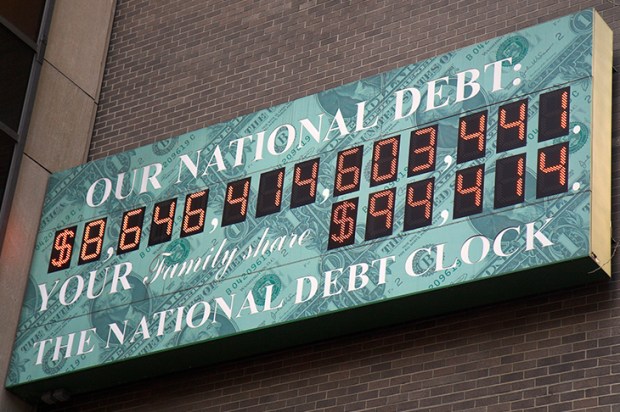

Australia had no net debt as recently as the early-2000s. Today, gross debt is scraping the $1 trillion mark, an almost comic outcome if it weren’t so serious. And over the same stretch, just two budget surpluses were achieved, both constructed on the shifting sands of temporary revenue boosts and creative accounting, not genuine fiscal responsibility.

Back in 2005, federal spending was 24 per cent of GDP. It’s now 26.2 per cent and forecast to balloon to 27 per cent next year. That increase translates to an $86 billion surge in annual spending, even after adjusting for inflation. In 2005, real per capita revenue was $14,239 and spending was $13,470. By 2025, those numbers jumped to $18,131 and $18,842 respectively, a 40-per-cent increase in the real cost of government.

Are Australians receiving 40 per cent more in value for their taxes? Better services? Improved infrastructure? A world-class education system? Of course not. But there are more bureaucrats, more forms, and more ‘initiatives’ that go precisely nowhere.

With borrowing costs hovering around 4.3 per cent, the annual interest bill alone is over $40 billion, a sum that could fund meaningful reform in education, healthcare, or infrastructure. Instead, it is servicing a tab Australian governments are too weak to stop running up.

The old debt ceiling, while imperfect, at least demanded a moment of reflection. Initially pegged at $75 billion in 2007, it was incrementally raised: $200 billion in 2009, $250 billion in 2011, and $300 billion in 2012. Each increase required parliament to engage in at least a charade of responsibility. Then came 2013. Newly elected and still basking in the glow of its ‘fix the budget’ rhetoric, the Abbott government ran straight into the $300 billion ceiling.

Treasurer Joe Hockey demanded a ludicrous jump to $500 billion, could not get it through, and, in a move laced with irony, repealed the ceiling. Since then, federal borrowing has been limited only by the imagination of public servants and the cowardice of politicians.

Reintroducing a debt ceiling today would not ban borrowing but would reintroduce a circuit breaker. A pause button. A public reckoning. A rare opportunity to ask: Should we keep doing this?

Knowing that breaching the ceiling requires public debate and parliamentary approval creates a modest deterrent. It brings long-term thinking back into a political system dominated by short-term sugar hits and electoral gimmickry.

A revived debt ceiling could serve as a proxy voice for future generations, those unborn or currently too young to vote but destined to pay the bill. It would help transform abstract fiscal concerns into real political pressure. Because apparently, if our political class are not forced to think past next Tuesday, they simply won’t.

Australia used to pride itself on sober, responsible economic management. Reinstating a debt ceiling would not just be symbolic but would be a declaration that there is concern about the future. It would remind Australians that debt is not just a background figure but a hard limit on what future governments will be able to do.

There was a time when both moral and institutional forces kept governments vaguely honest. The Burkean ideal of preserving society for those yet to come was more than a dusty principle. Today we’re not just bequeathing a mess; we’re burning the instruction manual for how to fix it. The collapse of education isn’t just ironic but strategically disastrous.

In 1850, Frédéric Bastiat warned, ‘When plunder becomes a way of life, society eventually creates a moral code and legal system that justifies it.’ Fast forward 175 years, and Australia is delivering on that prophecy, one handout and one empty promise at a time.

Unless accountability, fiscal restraint, and basic economic literacy, are recovered, the legacy left won’t be a nation but a bill. And good luck to the kids figuring out how to pay for it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.