In October 1945, towns and cities across the United States celebrated ‘A Tribute to Victory Day’ in celebration of the United States’s military victory over Nazi Germany and imperial Japan. The biggest event was held in Los Angeles and broadcast live across the country. In scenes ‘reminiscent of the pre-war Nazi rallies at Nuremberg’, Iain MacGregor writes, more than 100,000 people crammed into the Memorial Coliseum to watch the ‘cinematic legend’ Edward G. Robinson lead a massive cast on giant stage sets recreating key moments of the defeat of the Axis powers. For the evening finale, in the glare of searchlights, three Boeing B-29 Superfortresses flew low over the stadium and, as the audience gasped, a huge mushroom cloud rose behind the stage. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, I give you…Hiroshima!’ Robinson boomed.

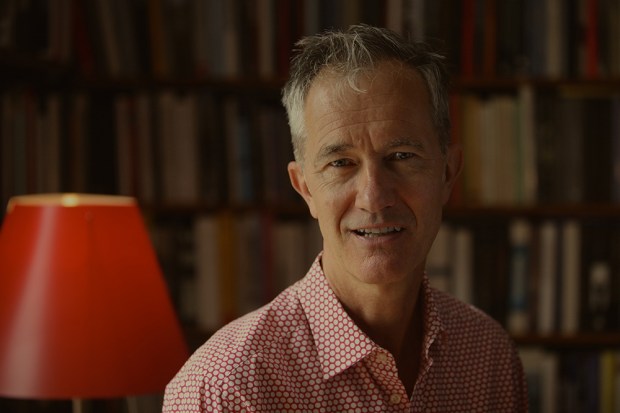

Published to coincide with the 80th anniversary of the first use of the atomic bomb as a weapon of war, The Hiroshima Men tells of the ‘quest’ to develop the bombin a gripping, challenging and sometimes provocative manner. With the help of new research and fresh voices, MacGregor traces the story from the discovery of nuclear fission in 1938 through to the decision to use it and the instant destruction of Hiroshima at 8.15 a.m. on 6 August 1945.

The inclusion of Japanese voices is a vital ingredient often missed from earlier accounts. Readers of MacGregor’s The Lighthouse of Stalingrad will find much to admire in this new book, which benefits from his ability to reframe the grand narratives of earlier lengthy books into accessible ‘micro-narratives’ told through eyewitness accounts, describing scenes not easily forgotten. The author’s decision to begin with his interview of the 87-year-old Michiko Kodama, one of the few remaining survivors of 6 August, means that the bookopens under the pall of a mushroom cloud that is impossible to ignore.

MacGregor sweeps us through this epic tale by cutting quickly and sharply between the stories of key individuals – some familiar, some less so. There is Dr Alexander Sachs and his almost comic struggle to attract the attention of Franklin D. Roosevelt; and there is Einstein’s letter warning of the danger of Nazi Germany developing nuclear weapons and urging America to do the same. Henry Luce, the publisher of Time and Life magazines, decided to take a chance on the journalist and future Pulitzer Prize-winning writer John Hersey and send him to cover his first war. Colonel Leslie Groves, after building the Pentagon, was given the job of directing the atomic bomb project (‘Oh, that thing’) against his will. The following month he appointed Professor J. Robert Oppenheimer to lead the Manhattan Project’s weapons laboratory, against advice from the intelligence services.

MacGregor also has a gift for juxtaposition. In a chapter titled ‘The Role of a Lifetime’, he introduces us to Lieutenant Colonel Paul Tibbets. He was an American pilot who had to be smuggled out of North Africa by his friends after he publicly humiliated the well-connected Colonel Laurie Norstad when he refused to fly a suicidal low-level raid on a German air base. ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do,’ Tibbets told his superior. ‘I’ll lead that raid myself at 6,000ft if you will come along as my co-pilot.’ Tibbets, we learn, went on to pilot the Enola Gay, named after his mother, which dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

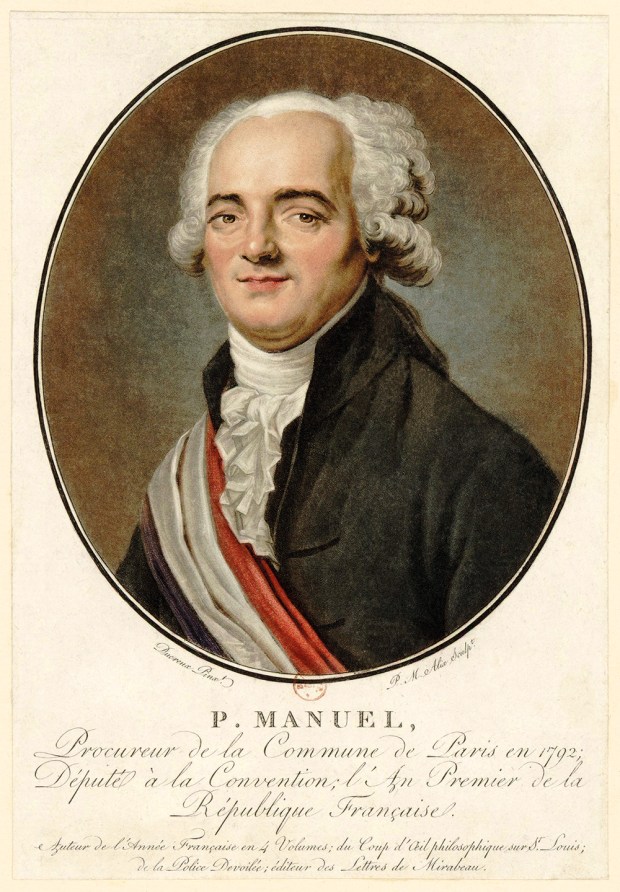

In the next chapter, ‘The Good Mayor’, we meet Senkichi Awaya. He was a Christian, a career civil servant, loyal to the civilian government of Japan and distrusted by its military government – ‘many men had been assassinated for less’ – who relocated his family to Hiroshima to begin his role as mayor. ‘He didn’t know it yet, but it would be his final civic duty.’ In similar style, MacGregor tells the story of the B-29 strategic bomber and the rise of American air power in short segments, in effect turning the bomber into another character in the story.

The memory of the great Victory Day celebration was quickly buried when the terrible truths came to light

While MacGregor struggles at times to capture the fighting that Hersey witnessed in the Pacific and Europe, he is soon on firmer ground. As in The Lighthouse of Stalingrad, he evokes the chaotic and unrelenting nature of war in claustrophobic set-piece scenes that build to a climax – from the battle of Iwo Jima or the firebombing of Tokyo to the flight of the Enola Gay and the destruction of Hiroshima. But it would have been good to have included a voice from the military-dominated government of Japan that refused to surrender before and immediately after Hiroshima.

MacGregor is fascinated by the link between memory and emotion. So it is appropriate that the last story in the book, Hersey’s race to reveal the true extent of the destruction of Hiroshima and the horrific deaths and injuries caused, is one of the most gripping of all. He famously published his 30,000-word account, simply titled ‘Hiroshima’, in the New Yorker on 31 August 1946 to critical acclaim. The memory of the previous October’s ‘Tribute to Victory Day’ was quickly buried as the terrible truths were brought to light.

For the 80th anniversary of the bombing, it would have been easy for MacGregor to write a worthy but dull tome. The Hiroshima Men is anything but that. It is a impeccably researched and compelling account of the first use of nuclear weapons in war, and a timely reminder of the horror they unleash- ed on the world.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.